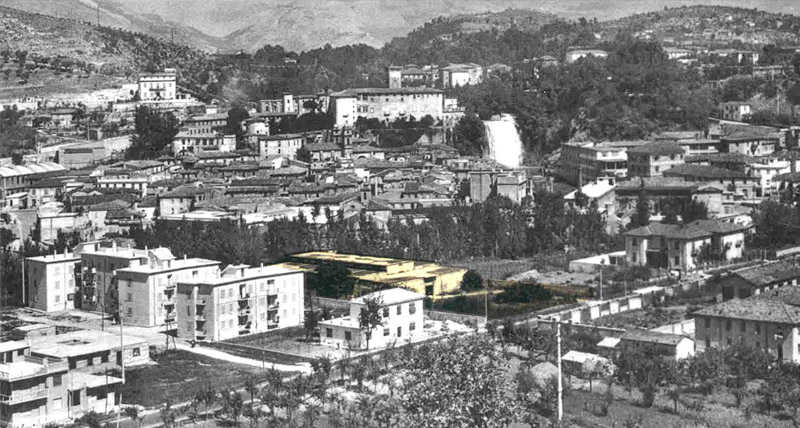

view of Isola del Liri (FR – Italy) in the 1960s

* * *

Isola del Liri is a charming small town in Lazio that takes its name from the particular configuration of its urban center, framed by two branches of the Liri River. The paper and wool industries have had a tradition in its history, but the name of Isola del Liri is known today for another reason. Readers from all over the world who pick up the books of Maria Valtorta’s Work, now translated into about thirty languages, see the name of Centro Editoriale Valtortiano, the Italian publishing house based in Isola del Liri, which publishes them itself or allows others to publish them. At the beginning of the 20th century, a printing house was founded in Isola del Liri by the initiative of Arturo Macioce, who, after a few years, welcomed as a partner his young brother-in-law Michele Pisani, brother of his wife. The “Società Tipografica A. Macioce & Pisani,” abbreviated as STAMP, became renowned for the precision of its printing and bookbinding, mainly commissioned by Roman Catholic institutions. In 1946, Macioce, fifteen years older than his brother-in-law and partner, retired, dissolving the company, whose activity continued with the individual business called “Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani,” which resumed printing books on behalf of pontifical publishers, general curias of religious orders, Catholic cultural institutes, and Catholic associations. (E.P.)

In 1952, Maria Valtorta entrusted the publication of her Work to the ‘Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani’. Emilio Pisani, son Michele’s son, took care of it, and in 1956, the first volume was printed.

The typographic composition of a book was done with the mechanical linotype system. The linotype operator would read the text on the sheet placed on the lectern and type it on the machine’s keyboard. The linotype mechanism was complex and fascinating due to the perfect sequence of its phases, up to the point of expelling, one by one, the lead lines. These lines were then linked together to form a page.

The raw material for the linotype was lead, melted in a crucible, continuously fed by the lead lines from books already printed and assembled. After printing a book for a predefined number of copies, the lead pages were stored for a possible reprint; but sooner or later, they had to be melted down to ensure the raw material necessary for the linotype did not run out.

Valtorta’s Work was in its first edition. It was thought that it could be composed and printed in only three volumes, but there was no precise idea of its size. When 1200 pages had been composed, it was realized that much was still missing to complete the material intended for the first volume. Thus, the volume had to be closed at that point and the edition was rethought in four volumes instead of three (the second to fourth volumes, each 900 pages).

The first volume of the Work, published in 1956, was a ‘brick’ of approximately 17×24 cm, with a thickness of nearly 7 centimeters. On the gray cardboard cover stood out the title without any graphic decoration or the author’s name. The text pages were printed in tight characters. The volume had all the characteristics of a literary product destined to fail, and yet it was followed by the second volume in 1957 and the third in 1958. The fourth and final volume was in the process of being composed (it would be released in 1959) when the thousand printed copies of the first volume were exhausted. Reprinting the volume was not possible, as the lead pages had been dismantled not only to feed the linotype but also because it was already thought to recompose the entire Work in a new carefully revised edition and divided into a more manageable number of volumes. (E.P.)

view of Monte San Giovanni Campano (FR – Italy) (photo: F. Bianchi)

Within the ‘Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani’, Emilio was primarily dedicated to editorial work, while his younger brother, Ettore, handled the technical and production aspects. Concerned about the growing difficulties, the young and enterprising Ettore hurried to propose new printing systems to improve the management of the entire production system.

This led to the installation of the first offset printing machine. But first, the old lead matrices had to be converted into new photosensitive supports (films and plates).

Following the advice of their maternal uncle, Father Raffaele, the Pisani brothers hired a young deaf-mute from Monte San Giovanni Campano, a town not far from Isola del Liri.

Antonio Bottoni, as he was called, was entrusted with the task of photographically reproducing all the pages of the Work, and to be able to start printing with the new equipment, he also had to devote himself to preparing the photosensitive plates.

In the printing house, a small darkroom was set up (these supports could not be exposed to daylight) and, always accompanied and supported by Ettore Pisani, Antonio spent entire days in the dark, going through the various phases to produce the negatives, developing, fixing, and again, the photographic positive.

The days turned into weeks, then months, and finally years. Always in search of the highest quality, the entire work was repeated a second time.

Antonio remained in service at the ‘Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani’ until his retirement. He passed away on July 11, 2024, at the age of 77. A sensitive person always available to others, he was a remarkable artist in woodworking and was also a mentor for the new generations who joined the ‘Tipografia Editrice M. Pisani’ in the 1980s.